Programação em cartaz

Exposição

Ateliê

de Restauro

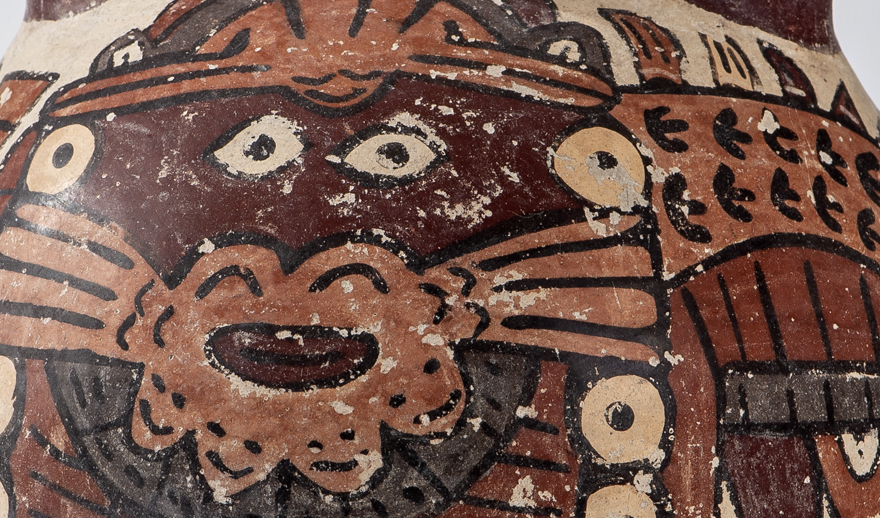

A partir do dia 30 de abril, a Casa Museu Eva Klabin inaugura o Ateliê de Restauro. A iniciativa tem como objetivo ampliar o contato do público com os processos de restauração e conservação do acervo da casa. Neste ano, os visitantes poderão acompanhar de perto as práticas técnicas realizadas nas obras Pré-colombiana da nossa coleção. Confira!

Oficina

Oficina Experimental

de Restauro

No mês de maio, oferecemos a Oficina experimental de Restauro para toda a família!

Programação musical

Glenda Carvalho e Katia Balloussier

Concertos de Eva

Vem aí mais uma edição do ´Concertos de Eva´! No dia 10 de maio, receberemos Glenda Carvalho (violoncelo) e Katia Balloussier (piano) para o recital ´Contrastes modernistas: um legado duradouro´.

Programação musical

Yoùn

Pôr do sol

No dia 31 de maio, receberemos o duo YOÙN para a segunda edição de 2025 do projeto ‘Pôr do Sol’!